A Tale of Two STEM Women

Ada Lovelace Day is a day for celebrating the achievements of women in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering and Math) fields. Recently, the New York Times published a fantastic article by Eileen Pollack, “Why Are There Still So Few Women in Science”. Women were leaving the profession not because they weren’t gifted but because of the “slow drumbeat of being under-appreciated, feeling uncomfortable and encountering roadblocks along the path to success”. In summary, the problem comes down to a lack of adequate support and encouragement for STEM women, whose confidence therefore slowly erodes over time, like limestone in an acid rain. Instead of beautiful stalactites however, we’re left with the ‘leaky pipeline’; the phenomenon where, although there appears to be gender parity, or even a majority, in the number of women in STEM fields at the undergraduate level, the senior staff ends up being almost predominantly male; the women have ‘leaked’ out of the pipeline.

I want to illustrate why support and encouragement is vital for women in STEM by presenting two stories. They are old; from the late 1800s and early 1900s, but their message remains as relevant today as it did back then.

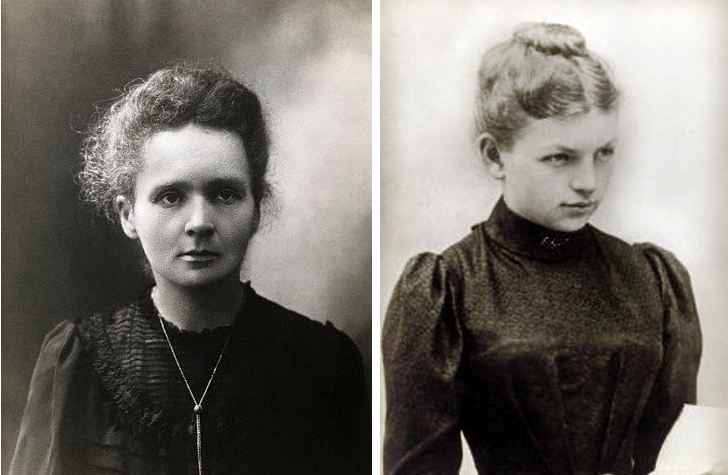

For many people outside STEM fields, Marie Curie remains the go-to female scientist. Everyone knows about her fantastic work ethic and achievements, the only woman to win two Nobel Prizes, for Chemistry and Physics. A large part of her success comes from an uncompromising desire to excel at the things that she was passionate about, coupled with having people in her life who encouraged her to do so. Notably, both her father and grandfather were educators who encouraged her to pursue mathematics and physics, subjects that she wanted to study. She also married Pierre Curie, who treated her as an equal partner in every sense of the word. They supported and encouraged each other’s work constantly, and together were more successful than either would have been apart.

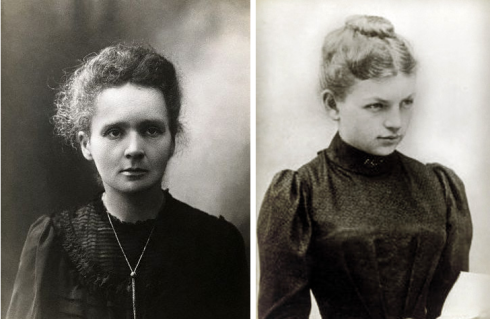

In contrast, the story of Clara Immerwahr is far more tragic and, to me, illustrates the loss faced by humanity when women in STEM are not encouraged. Clara Immerwahr was a chemist, and also the first woman to earn a Ph.D from the prestigious University of Breslau (now Wrocław). But unlike her (often-cited) contemporary Marie Curie, Immerwahr had the misfortune to marry Fritz Haber, who was definitely not an open-minded man like Pierre Curie was.

Fritz Haber is known for his contradictory contributions to society; on the one hand he is responsible for the Haber process by which ammonia is synthesized; this has applications in fertilizer production and is essential to our agriculture (he won the Nobel prize for this in 1918); on the other hand the scientists at his institute developed the gas Zyklon A, which the Nazis ‘refined’ into the notorious Zyklon B used in their concentration camp gas chambers. Haber was guilty too, of the development of other chlorine-based gases, infamously used in the German attack against the French in Ypres. Haber also developed Haber’s Rule, a horrific method to quantify the relationship between gas concentration, exposure time and death-rate. The mind recoils at the thought of what gathering data for this involved.

Haber’s views on women were no better than his views on gas warfare. According to an historian, Immerwahr “was never out of apron”, and she once confided to a friend about her subservient role; “It has always been my attitude that a life has only been worth living if one has made full use of all one’s abilities and tried to live out every kind of experience human life has to offer. It was under that impulse, among other things, that I decided to get married at that time… The life I got from it was very brief…and the main reasons for that was Fritz’s oppressive way of putting himself first in our home and marriage, so that a less ruthlessly self-assertive personality was simply destroyed”. She ended up translating his manuscripts into English and providing technical support on his nitrogen projects, her own dreams and potential ignored and forgotten; although she drew the line at helping him with his poison gas work.

Immerwahr was repulsed by Haber’s growing obsession with the development of poison gas. She confronted him numerous times but her pleas fell on deaf ears. On May 2nd 1915, she quarreled violently with Haber when she found out that he had come home for just the night and was leaving again in the morning to direct more poison gas attacks on the Eastern front. In the early hours of the morning, Immerwahr walked into the garden with Haber’s army pistol and shot herself in the chest. Haber of course did not let this inconvenience him, and left as planned the next morning without even making any funeral arrangements.

When I first read this story, I was struck by how often we focus on happy stories like Marie Curie’s, and how the story of someone like Clara Immerwahr remains largely forgotten. She had a tremendous amount of potential, as evidenced by her being the first female to receive a Ph.D at the University of Breslau, an endeavor that is certainly not for the faint-hearted even now. One can only wonder at the ‘might-have-beens’ if she had had the same support and encouragement that Marie Curie did, if she had not married Haber, or if Haber had been a different kind of person. These examples highlight that talent alone is not enough; we need to encourage that talent by promoting equality and recognizing our own biases when it comes to women in STEM.

For Ada Lovelace Day, let us recognize that we not only have to celebrate women in STEM, we have an imperative to actively support and encourage them.

Samarasinghe B (2013-10-15 00:22:56). A Tale of Two STEM Women. Australian Science. Retrieved: Apr 25, 2024, from http://australianscience.com.au/women-in-science-2/a-tale-of-two-stem-women/

Follow

Follow

Enjoyed reading it. The author does have a point and as she explains, Clara Immerwahr’s story is in fact heart-rending. However, I can’t believe that Marie Curie’s story was such a ‘happy’ one from what I’ve read about her life. She had to do her work while there was a major-scale war going on, and her daughters were not with her (though her husband may not have been an uncooperative person).

Great article! So glad my friend Charlie posted that on his Google+ page.